Photo, Left to right: Debra Schmidt Bach, PhD; Leah Prescott, MLS; Michael P. Dyer, MA; Akeia de Barros Gomes, PhD; Elysa Engelman, PhD

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM ANNOUNCES THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR MARITIME STUDIES

LED BY AKEIA DE BARROS GOMES, PhD, THE WILLIAM E. COOK VICE PRESIDENT FOR MARITIME STUDIES; INITIATIVE UNITES MUSEUM’S RENOWNED HIGHER EDUCATION PROGRAMS

Museum Appoints Leah Prescott, MLS, as Senior Administrator of Library Resources, Debra Schmidt Bach, PhD, as Director of Exhibitions, Elysa Engelman, PhD, as Director of Research and Scholarship, and Michael P. Dyer, MA, as Curator of Maritime History

Mystic, CT. [September 25, 2024] – Mystic Seaport Museum announces the launch of the American Institute for Maritime Studies (AIMS), an initiative that consolidates the Museum’s scholarship in maritime studies and elevates its role as the nation’s leading maritime research facility and academic institute. AIMS will strengthen the Museum’s graduate and undergraduate programs, including fellowships and internships through the newly created Department of Research and Scholarship. In addition to being the nation’s premier location for maritime scholarships, there will be a particular emphasis on making collections (both objects and manuscripts) more publicly accessible for researchers and the general public. AIMS will engage with institutions of higher education, including the Ruth J. Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice at Brown University, Williams College, and the University of Connecticut.

The Museum has appointed Dr. Akeia de Barros Gomes as the William E. Cook Vice President for Maritime Studies at AIMS. De Barros Gomes joined the Museum in 2021 as Senior Curator of Maritime Studies. The Museum has also named Leah Prescott, MLS, as Senior Administrator of Library Resources at AIMS, Dr. Debra Schmidt Bach as Director of Exhibitions at the Museum, Dr. Elysa Engelman as Director of Research and Scholarship, and Michael P. Dyer, MA, Curator of Maritime History and Instructor, Frank C. Munson Institute of Maritime History.

“I am thrilled to lead the American Institute for Maritime Studies as we embark on this important new chapter for the Museum,” says Dr. de Barros Gomes of her new role. “AIMS represents a significant step forward in the Museum’s mission to enhance the scholarship around maritime histories and to tell stories that have been passed from generation to generation.”

AIMS will build upon ongoing research opportunities at the Museum, including fellowships, internships, and visiting scholars, by creating additional opportunities for community engagement and academic initiatives, including publications. Earlier this year Mainsheet: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Maritime Studies debuted. This biannual publication, available both online and in print, sets itself apart with its multidisciplinary approach, global themes and accessibility, and innovative design and distribution. Mainsheet offers a unique platform for scholars worldwide to explore maritime issues spanning the past, present, and future. AIMS scholars and staff will broaden their research through robust connections with national and international universities and museums, and will explore topics related to maritime cultural connections, maritime art, and social and economic issues through a contemporary lens.

As the William E. Cook Vice President for Maritime Studies, Dr. de Barros Gomes will be responsible for bringing strategic vision and thought leadership to the Institute. She will oversee professionals dedicated to advancing the Museum’s academic presence in maritime studies and share those findings and stories with local and broader Museum visitors through exhibitions and programming. AIMS will also continue Dr. de Barros Gomes’s outreach to local communities to engage with oral histories. Previously as the Museum’s Senior Curator of Maritime Studies, Dr. de Barros Gomes was lead curator of the exhibition Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea, on view at the Museum through April 2026. She is also the co-Director of the Museum’s Frank C. Munson Institute of American Maritime Studies along with Michael P. Dyer. Before joining Mystic Seaport Museum, she was Curator of Social History at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. She received a PhD and MA in Anthropology with a focus in Archeology from the University of Connecticut in 2008.

Leah Prescott, MLS, has been appointed the new Senior Administrator of Library Resources. Prescott was previously the Associate Director for Collections and Co-Interim Director at the Harvard Law School Library and served as Associate Director for Digital Initiatives and Special Collections at Georgetown Law Center. Previously at Mystic Seaport Museum, she held several positions over two decades, including Manuscripts and Archives Librarian, Collections Information Technology Coordinator, Information Technologies Librarian, Manuscripts Assistant, and Museum Interpreter. Prescott holds a Master of Library Science and Information Studies from Syracuse University and a BA in American History from the University of Connecticut. She has been a Certified Archivist since 2005 and actively participates in the National Digital Stewardship Alliance, where she co-chaired the Infrastructure Interest Group from 2020 to 2022.

Debra Schmidt Bach, PhD, has been appointed as the new Director of Exhibitions. Bach was previously the Curator of Decorative Arts and Special Exhibitions at the New-York Historical Society, where she curated and collaborated on numerous popular culture and social history exhibitions, including The Art of Winold Reiss: An Immigrant Modernist; Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere; and First Jewish Americans: Freedom and Culture in the New World. Bach lectures widely, has written numerous essays, articles, and blogs, and has contributed to exhibition catalogs and popular culture anthologies, including “Of Great Renown: The History of Rheingold Beer,” in The New York Mets in Popular Culture (McFarland & Co., 2020). Bach received an MA in American Studies from Columbia University and a PhD with a focus on material culture and design history from the Bard Graduate Center in 2015.

Michael P. Dyer, MA, has been appointed the new Curator of Maritime History. Dyer was most recently Curator of Maritime History at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, where he curated several exhibits including most recently the exhibition All Hands: Yankee Whaling and the U.S. Navy (2023–24). He was an editor of Vistas: A Journal of Art, History, Science, and Culture, published by the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and is author of several monographs including “O’er the Wide and Tractless Sea”: Original Art of the Yankee Whale Hunt (New Bedford, 2017), and was previously an instructor in Maritime History at the Northeast Maritime Institute at Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Dyer was also a USA Gallery Inaugural Fellow at the Australian National Maritime Museum in 2008, and a 38th Voyager onboard the bark Charles W. Morgan of Mystic, Connecticut, in the summer of 2014.

Elysa Engelman, PhD, has been appointed the AIMS Director of Research and Scholarship. This new position entails working with the curatorial team to produce scholarly output; organizing academic lectures, symposia, and conferences; developing scholarly publications; and managing AIMS-centered internships and fellowships. Engelman was previously Exhibits Researcher/Developer at Mystic Seaport Museum and then Director of Exhibits. She has a doctorate from Boston University in American and New England Studies and a BA from Yale University in English and Theater Studies. Engelman has taught courses in Women’s Studies, Public History, and the Historian as Detective at the University of Connecticut at Avery Point and written on wide-ranging topics including the maritime Underground Railroad, Route 66, Lydia E. Pinkham, and the threat of sea-level rise to maritime museums.

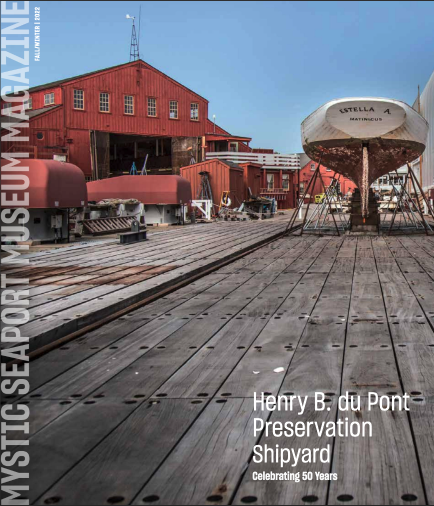

About Mystic Seaport Museum

Mystic Seaport Museum is the nation’s leading maritime museum. Founded in 1929 to gather and preserve the rapidly disappearing artifacts of America’s seafaring past, the Museum has grown to become a national center for research and education with the mission to “inspire an enduring connection to the American maritime experience.” The Museum’s grounds cover 19 acres on the Mystic River and include a re-created New England coastal village, a working shipyard, formal exhibit halls, and state-of-the-art collection storage facilities. The Museum is home to more than 500 historic watercraft, including four National Historic Landmark vessels, most notably the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan.

For more information, please visit mysticseaport.org and follow the Museum on Facebook, X, YouTube, and Instagram.

###

Parking in downtown Mystic has been a growing challenge and the Museum is now working Laz Parking to alleviate traffic and parking issues during the peak tourist season. The south half of the Museum’s South Lot, located along Route 27 will be available to downtown visitors for $10 per day (Museum members and visitors will continue to enjoy free parking).

Parking in downtown Mystic has been a growing challenge and the Museum is now working Laz Parking to alleviate traffic and parking issues during the peak tourist season. The south half of the Museum’s South Lot, located along Route 27 will be available to downtown visitors for $10 per day (Museum members and visitors will continue to enjoy free parking). This fee includes a free shuttle bus service to downtown Mystic which will run from 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. and may be adjusted as demand is established over the course of the season. Downtown Mystic visitors will be prompted through parking lot signage to pay via the Laz Parking App or through Text to Donate. Proof of payment will be required to gain shuttle access.

This fee includes a free shuttle bus service to downtown Mystic which will run from 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. and may be adjusted as demand is established over the course of the season. Downtown Mystic visitors will be prompted through parking lot signage to pay via the Laz Parking App or through Text to Donate. Proof of payment will be required to gain shuttle access.