Monstrous

Whaling and Its Colossal Impact

Now on Exhibit

Collins Gallery, Thompson Exhibition Building

Step into the world of 19th-century American whaling with Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact, a powerful new exhibition that explores the sheer scale—physical, economic, and human—of the nation’s whaling industry and its legacy.

Explore hundreds of striking artifacts from the Museum’s renowned whaling collections—tools, old photographs, ship models, documents, and more—most of which have never been exhibited together before. Hefty iron trypots, harpoons, darting guns, and blubber hooks tell the story of the extraordinary lengths commercial whalers went to harvest oil-rich blubber and spermaceti. These items speak to the staggering risks and resource demands of an industry that lit America’s lamps and greased its machines for over a century.

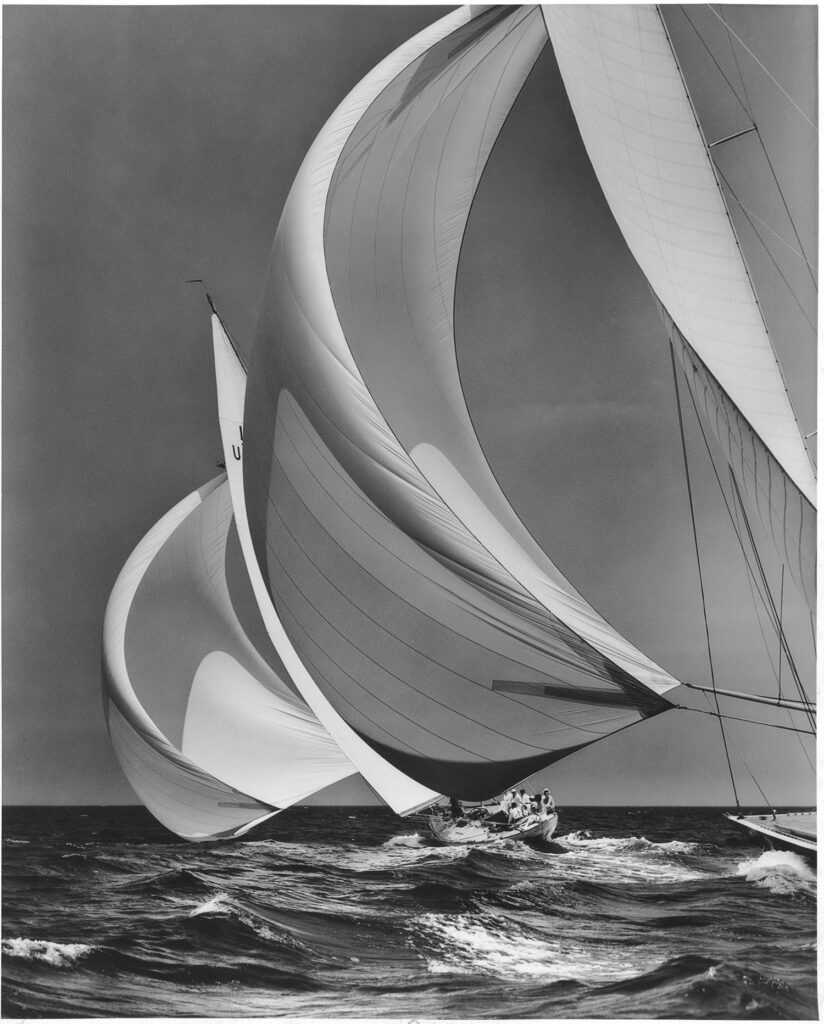

Through vivid paintings, lithographs, and rare historic photographs, Monstrous brings to life the perilous activities involved in chasing, capturing, and processing whales—many of these scenes taken from our Robert Cushman Murphy and H. S. Hutchinson & Co. photography collections. Visitors will come face-to-face with images of whalers “cutting in” and “trying out” aboard floating factories, viewed alongside the very tools used in the hunt.

At the forefront of the exhibition is Or, The Whale, a monumental 51-foot mural by artist Jos Sances. Shaped like a life-sized sperm whale and created from 119 intricately inscribed scratchboard panels, the mural immerses viewers in a visual journey through three centuries of American industrialism. Influenced by Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and Rockwell Kent’s iconic illustrations, Sances’s work weaves together scenes of industry, innovation, and ecological transformation. Visitors can dive deeper into the mural through an artist video and interactive digital experience powered by ThingLink.

The exhibition also features exquisite consumer goods made from whale byproducts—items of both beauty and utility. See ornate examples of scrimshaw, including knitting needles, corset busks, boxes, and a rare scrimshaw lathe and bandsaw. These artifacts underscore how deeply whale oil and materials were embedded in 19th-century daily life.

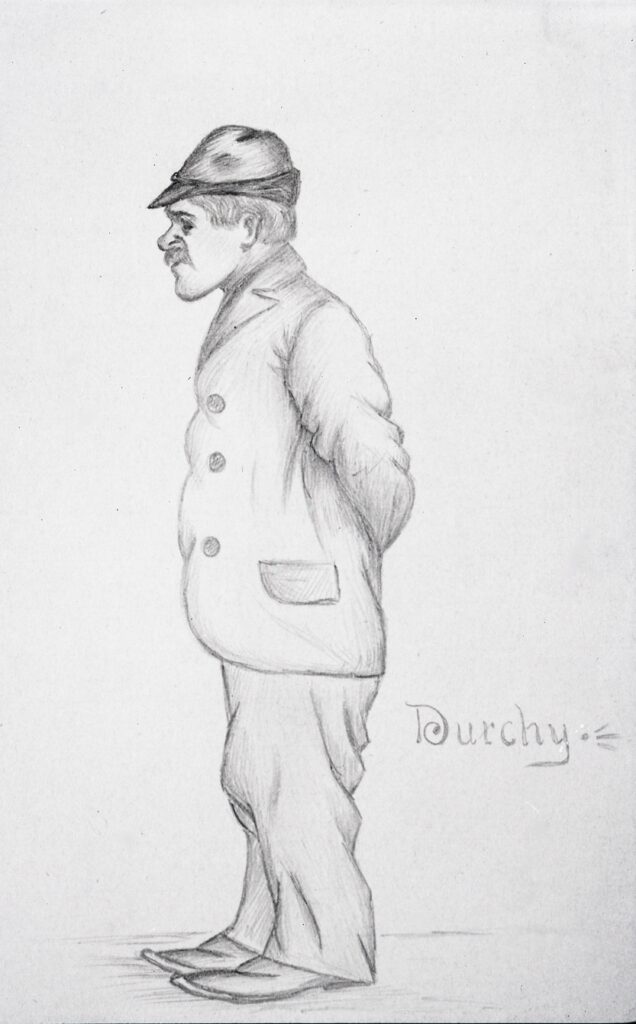

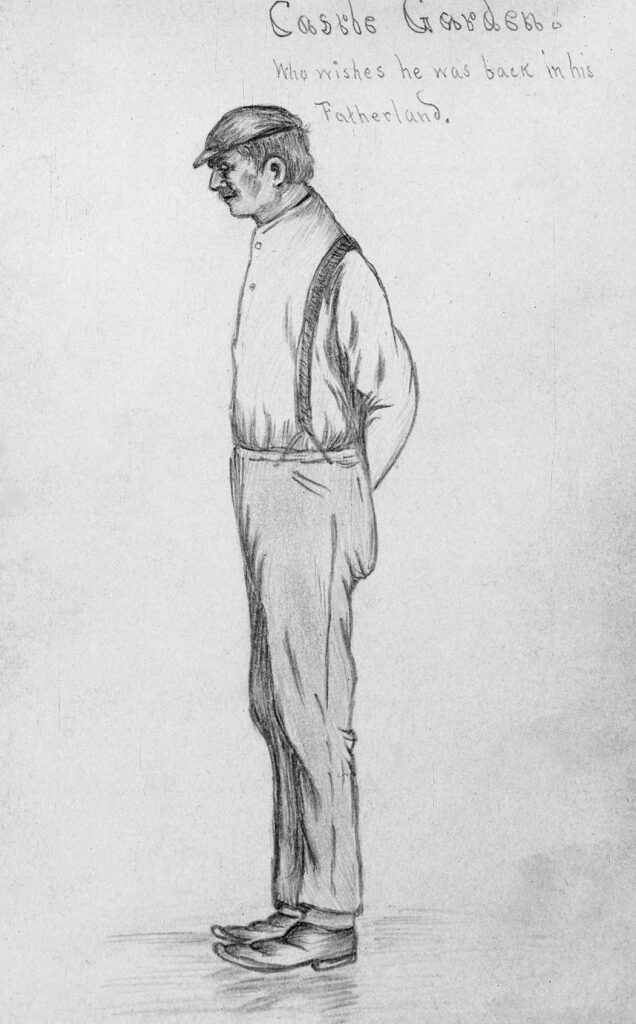

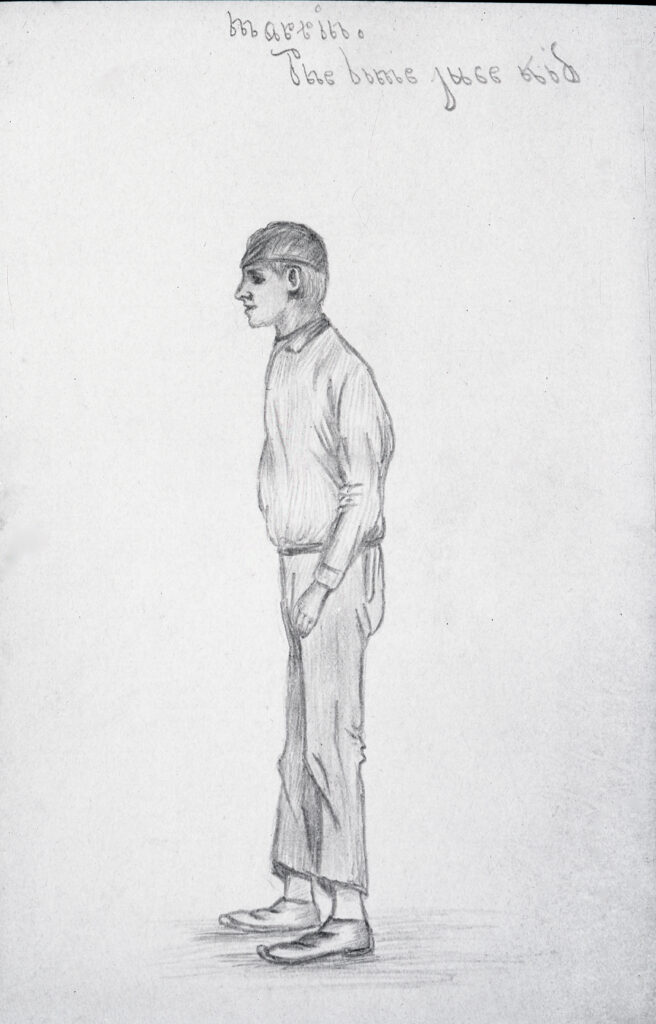

Monstrous goes beyond tools and trade to tell personal stories of the people behind the industry. Discover the lives of multicultural whaling crews, including Cape Verdean whalers like Antoine DeSant, who settled in New London in 1860. Learn about women who defied conventions by joining whaling voyages not only as wives and mothers but also as navigators, nurses, and log keepers. One remarkable figure, Charlotte “Lottie” Church, signed on as an assistant navigator in 1909 and was the last woman to sail aboard the Charles W. Morgan during its whaling career.

Two extraordinary whaling logs offer deeper insight into life at sea—one from the bark Ohio (1875–78) complete with whale stamps, and another handmade in 1821 from burlap and sailcloth by a Cape Verdean whaler. These documents, along with models of whaling ships and samples of commercial whale oil, offer a comprehensive and moving look at an industry that helped shape our region and nation.

Don’t miss the chance to experience this bold and thought-provoking exhibition that blends art, history, and storytelling to explore whaling’s monstrous impact on the world—and the people—who built it.

A fully equipped whaleboat is on display in the shed on Chubb’s Wharf. The building, patterned after buildings on several of New Bedford’s whaling wharves, was constructed in 1982. The whaleboat came to the Museum aboard the Charles W. Morgan in 1941. It is not known whether it was ever actually used, though it was likely built before 1920. The boat contains the gear typically carried in American whaleboats of the 1880s, and whaling tools are displayed above the boat.

A fully equipped whaleboat is on display in the shed on Chubb’s Wharf. The building, patterned after buildings on several of New Bedford’s whaling wharves, was constructed in 1982. The whaleboat came to the Museum aboard the Charles W. Morgan in 1941. It is not known whether it was ever actually used, though it was likely built before 1920. The boat contains the gear typically carried in American whaleboats of the 1880s, and whaling tools are displayed above the boat. The whaleboat was a beautiful craft adapted for a brutal purpose. You can see that this light, strong, double-ended boat was packed with gear for hunting the whale. Whaleships like the Charles W. Morgan carried between three and five whaleboats, hanging in davits ready to use. Each boat was operated by one of the ship’s officers and five oarsmen. About 1,200 feet of whale line were coiled in two tubs, then run around a loggerhead at the stern and forward over the oars to connect to the harpoons–which the whalemen called irons–at the bow. When the forward oarsman, usually called the boatsteerer, got the call, he stood, braced his leg in the “clumsy cleat” notch near the bow, and darted his irons into the whale. This anchored the boat to the whale. He then made his way aft to take the steering oar, and the officer came forward to kill the whale once it grew tired from pulling the boat in a “Nantucket sleighride” or diving–“sounding”– to escape. The officer used a long-shanked lance to pierce the whale’s lungs and cause it to bleed to death. Once the whale rolled over, “fin out,” in death, the boat towed the whale to the mother ship to be processed.

The whaleboat was a beautiful craft adapted for a brutal purpose. You can see that this light, strong, double-ended boat was packed with gear for hunting the whale. Whaleships like the Charles W. Morgan carried between three and five whaleboats, hanging in davits ready to use. Each boat was operated by one of the ship’s officers and five oarsmen. About 1,200 feet of whale line were coiled in two tubs, then run around a loggerhead at the stern and forward over the oars to connect to the harpoons–which the whalemen called irons–at the bow. When the forward oarsman, usually called the boatsteerer, got the call, he stood, braced his leg in the “clumsy cleat” notch near the bow, and darted his irons into the whale. This anchored the boat to the whale. He then made his way aft to take the steering oar, and the officer came forward to kill the whale once it grew tired from pulling the boat in a “Nantucket sleighride” or diving–“sounding”– to escape. The officer used a long-shanked lance to pierce the whale’s lungs and cause it to bleed to death. Once the whale rolled over, “fin out,” in death, the boat towed the whale to the mother ship to be processed.

The 92-foot keel assembly from the whaleship Thames is set up on blocks in a shed within the Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard. The keel is the “backbone” and the starting point for the construction of a ship and so, displayed along the entire length of the keel, is an exhibit on the process of shipbuilding that takes visitors from the laying of the keel to her launching.

The 92-foot keel assembly from the whaleship Thames is set up on blocks in a shed within the Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard. The keel is the “backbone” and the starting point for the construction of a ship and so, displayed along the entire length of the keel, is an exhibit on the process of shipbuilding that takes visitors from the laying of the keel to her launching.